How the Stock Market Shapes the Real Economy — A 1,000-Word Deep Dive

The stock market is more than a daily scoreboard for investors. It’s a living mirror of expectations — about earnings, interest rates, technology, trade and geopolitics — and those expectations can ripple into the real economy in measurable and sometimes surprising ways. Understanding the transmission channels — how market moves affect spending, business investment, monetary policy and inequality — helps explain why moves on Wall Street matter to Main Street. Below, I unpack the most important mechanisms, the limits of market influence, and what recent research and policy practice tell us. (Investopedia)

1) The wealth effect: confidence translated into consumption (sometimes)

One of the most-cited links between markets and the economy is the “wealth effect.” When stock prices rise, households that own equities — directly or through retirement accounts — see their paper wealth increase. Feeling richer, some consumers spend more on big-ticket items or remodels, which supports GDP. Conversely, a sharp drop in markets can tighten household spending and slow growth. Economists find this channel exists, but its size varies: housing wealth historically has a stronger influence on consumption than financial assets, and the stock-wealth effect can be uneven across regions and income groups. That’s important because rising markets don’t automatically translate into broad-based increases in spending if the gains remain concentrated among wealthier households who have a lower marginal propensity to consume. (IMF, Investopedia)

2) Cost of capital and corporate investment

Stock valuations affect companies directly. Higher equity prices lower firms’ cost of capital, making it cheaper to issue shares for acquisitions or investment, and supporting expanded capital spending. When markets rally, corporate management and boards may be more willing to fund long-term projects because financing is more accessible. On the flip side, a sustained market slump can constrain investment, especially for firms that rely on equity markets rather than cash flow or bank lending. Research and practical experience show the relationship is real, but conditional: firms’ balance sheets, credit conditions, and expected returns all mediate whether a market rise translates into factories, R&D or hiring. (Investopedia, Federal Reserve)

3) Signaling and business confidence

Perhaps the most underrated link is the stock market’s role as a forward-looking barometer. Stock indices aggregate investor sentiment about future profits, demand and policy. Sharp market swings can change CEO expectations and boardroom decisions. A plunging index can prompt firms to delay hiring or freeze discretionary spending; a sustained rally can embolden expansion plans. Central banks and policymakers watch these signals too, because if markets start pricing in recession risks or a sudden policy shift, that can influence real outcomes even before fundamentals change. (Investopedia)

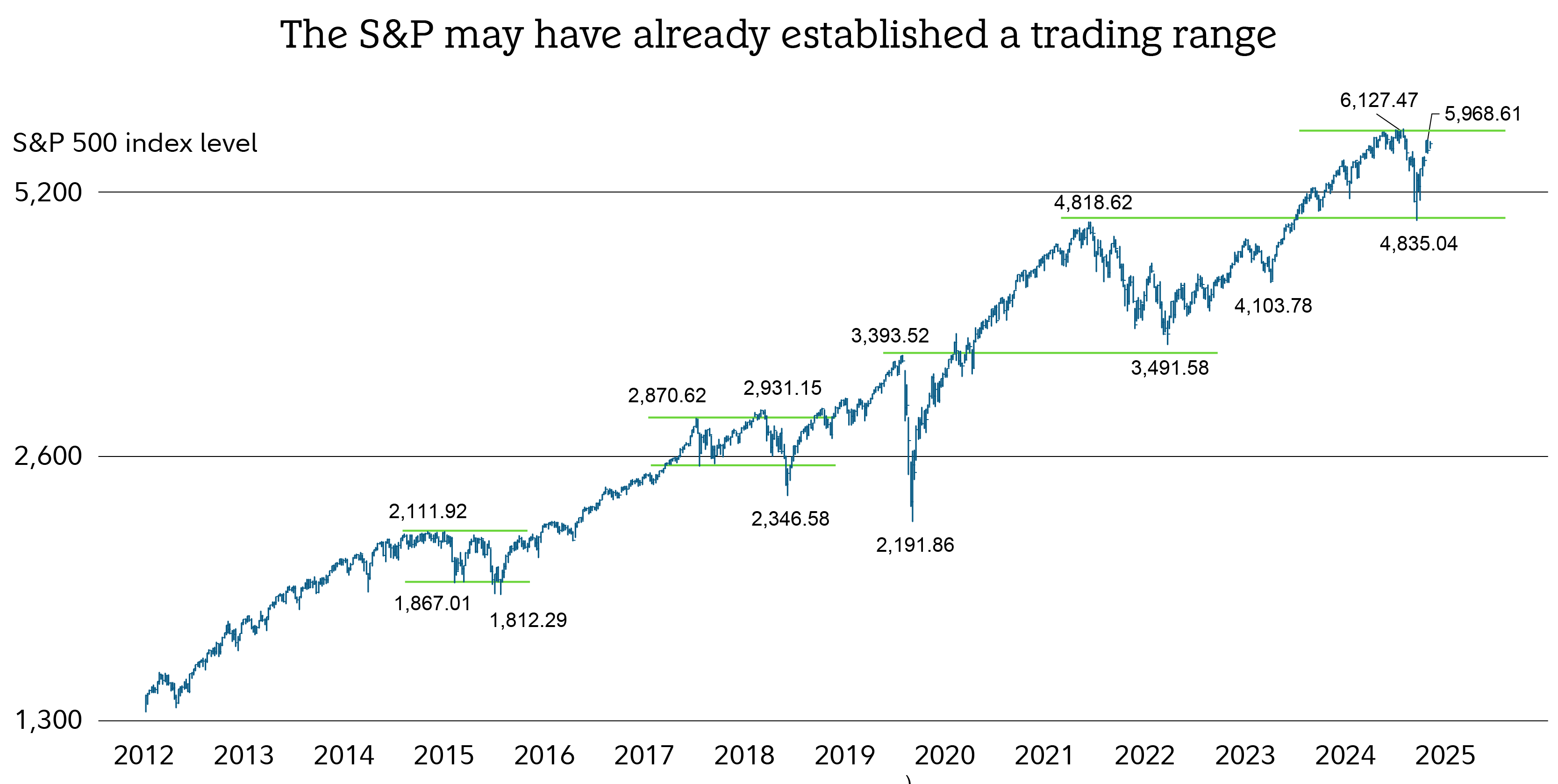

4) Monetary policy: the Fed listens, but not slavishly

Policymakers do not set policy to chase stock prices. Still, central banks monitor equity markets because market moves can alter financial conditions — through wealth, credit spreads and liquidity — which in turn affect inflation and growth. Academic work and central-bank research suggest the Federal Reserve responds to stock-price movements only to the extent those moves affect the macroeconomy (jobs, spending, inflation). In practice, large market disruptions (think 2008 or the COVID crash of 2020) can prompt central banks to ease aggressively to stabilize financial conditions. Meanwhile, anticipated rate cuts or hikes remain among the most consistent drivers of stock performance. (NBER, Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

5) Transmission through banks, credit and corporate behavior

Stock declines can tighten bank lending — especially to leveraged companies or sectors under stress — which restricts credit to households and small businesses. Volatility can also push up borrowing costs, curtail mergers and acquisitions, and make firms more conservative about long-term projects. Conversely, a buoyant market tends to lower risk premia and supports credit expansion, creating a virtuous loop for cyclical growth. However, that loop can amplify imbalances: cheap credit + rising equity prices can inflate asset bubbles that later unwind violently. (Federal Reserve)

6) Distributional effects and political economy

One reason the link between markets and the economy is contentious is distribution. Stock ownership is heavily skewed toward wealthier households and institutional investors. When markets soar, headline GDP numbers and corporate profits may look healthy while wage growth and middle-class living standards lag. That can fuel political backlash and shape policy debates over taxation, regulation and social spending. Policymakers therefore face a complex trade-off: market-friendly actions can boost investment and retirement balances for some, while leaving others feeling left behind. (Investopedia)

7) Limits and caveats: not everything is driven by stocks

Important caveats temper the market-to-economy story. First, correlation is not causation: both stock performance and economic health respond to common drivers like productivity, fiscal policy and global demand. Second, researchers find that the consumption response to stock-market gains is smaller than often assumed (housing tends to be more powerful). Third, modern economies face risks that don’t map neatly onto equity prices: supply-chain disruptions, climate shocks, or structural shifts in labor markets can weaken growth regardless of stock indices. Finally, policy tools matter — a central bank that reacts prudently to market stress can blunt real-world spillovers. (IMF)

8) Practical takeaways for readers and policymakers

For households: don’t treat daily market moves as a short-term guide for spending decisions. Retirement and long-term plans should be based on durable savings goals, not headlines. For businesses: monitor market sentiment but keep investment choices grounded in cash-flow projections and strategic need rather than transient equity momentum. For policymakers: market signals are useful inputs, but policy should weigh distributional effects and the quality of growth — not just headline GDP — when deciding on fiscal or monetary action. (Forbes)

Conclusion: an imperfect, powerful mirror

The stock market remains an influential — but imperfect — channel between financial markets and the broader economy. It affects consumption via wealth, corporate behavior via financing costs, and policy by signaling risks. Yet its power is bounded by distributional realities, alternative wealth channels like housing, and the broader macroeconomic context. Reading the market well means seeing it as a high-profile messenger, not an omnipotent engine: its signals deserve attention, but sound policy and planning require looking beyond the ticker to the fundamentals underneath. (Investopedia, IMF, Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

Sources & further reading: Investopedia primer on how the stock market affects the economy; Federal Reserve and NBER research on how policymakers react to market moves; IMF and academic papers on the wealth effect and consumption; practical summaries from major financial outlets. (Investopedia, NBER, IMF, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve)

Would you like me to (a) convert this into a visual one-page infographic, (b) create a 200-word executive summary for distribution, or (c) expand any section with charts and citations?